You have probably heard about chronic inflammatory states and some of their symptoms, body pain, fatigue, insomnia, depression, anxiety, mood disorders, weight gain/loss, among others (1). Inflammation is a reflection of the state of our immune system, and is closely related to the lifestyle and therefore the eating pattern you follow.

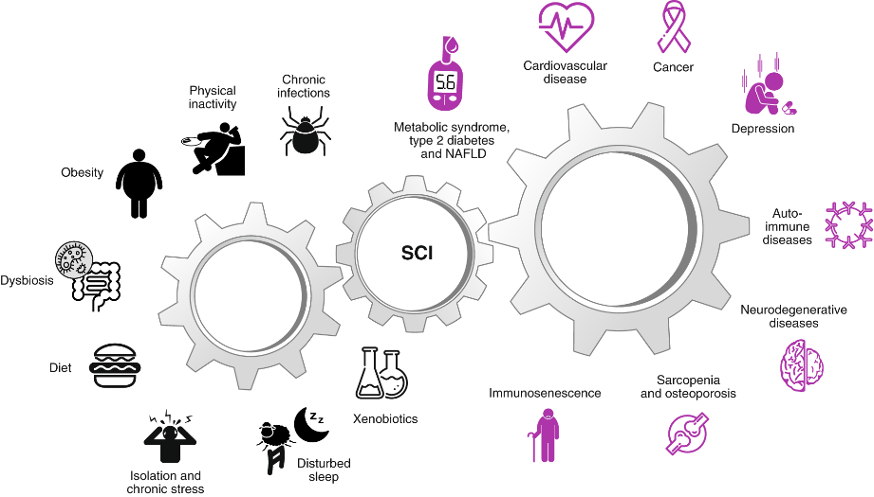

Although inflammation is an essential biological response of the immune system to injury and pathogens, over prolonged periods it can contribute to a number of health problems (2). In this article, we will explore how diet impacts inflammatory states and how the properties of some foods can support immune health and reduce inflammation.

Diet plays a crucial role in regulating inflammation; some foods can exacerbate inflammation, while others help reduce it (3). Thus, the Mediterranean4, Nordic (5), washoku (Japanese) (6) and jiangnan (southern Chinese) (7) diets are characterized by anti-inflammatory properties. These properties are mainly attributed to phenolic compounds such as ferulic acid, quercetin, kaemferol, cyanidin, epicatenin and others, present in foods such as olives and dark chocolate, capers and shallots, cumin and beans, strawberries and raspberries, cider and blackberries, respectively (8). Phenolic compounds in the diet allow the regulation of oxidative stress and therefore promote the reduction of inflammation in the body; an interesting academic article reviewed the content of anti-inflammatory compounds in foods and proposed a daily diet plan to achieve an optimal concentration of anti-inflammatory compounds (9).

Breakfast:

- Whole wheat bread; olive oil; Soy milk; Blackberries; Red currant. va; Soy milk; Blackberries; Red currant.

- Snack: Pomegranate juice; Chestnuts and pecans

Lunch:

- Black and green olive salad; tomato, vinegar; rhubarb; capers, olive oil.

- Lentils and steamed vegetables, lentils; black beans, carrots, tomato, shallots, olive oil, oregano, cumin and cloves.

- Rye bread

- Plum

- Dark chocolate

- Snak: Orange juice and pecans

Dinner:

- Grilled salmon and vegetables, Salmon; olive oil; eggplant, artichoke, rosemary.

- Rye breadGreen grapes

This is how we find numerous articles that define fruits and vegetables, which are rich in antioxidants, whole grains, rich in fiber, nuts and seeds, which provide healthy and anti-inflammatory fats, fish, with healthy fats such as omega-3 and, finally, herbs and spices (10–13) as a category of anti-inflammatory foods. These foods together and separately, favor the reduction of inflammation levels in the body.

On the contrary, research indicates that refined, highly processed foods and excessive alcohol have the effect of increasing blood glucose and increasing the blood content of inflammatory markers. These foods are related to cardiovascular problems, obesity and intestinal dysbiosis (14–16).

Scientific evidence highlights that following a diet rich in fiber and fermented foods can improve the health of the intestinal microbiome, which is essential to control inflammation. Probiotics and prebiotics play an important role in regulating the immune system and reducing inflammation (13).

High-quality foods are essential for a nutritious, balanced diet and for strengthening the immune system. Early diet plays a fundamental role in the intestinal and therefore immunological well-being of children. Fruit and vegetable purees are products that are designed to provide a rich source of anti-inflammatory nutrients that support general health and child well-being. Fruit and vegetable purees are an excellent way to incorporate a variety of vitamins, minerals and antioxidants into the diet of children and adults, contributing to healthy development and a balance of inflammatory states in our body. Adopting healthy eating habits is key to maintaining good health throughout life.

- Pahwa, R., Goyal, A. & Jialal, I. Chronic Inflammation. StatPearls (2023).

- Furman, D. et al. Chronic inflammation in the etiology of disease across the lifespan. Nat Med 25, 1822–1832 (2019).

- Fletcher, J. Anti-inflammatory diet: What to know. Medical News Today (2023).

- Panagiotakos, D. B., Pitsavos, C. & Stefanadis, C. Dietary patterns: AMediterranean diet score and its relation to clinical and biological markers of cardiovascular disease risk. Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases 16, 559–568 (2006).

- Lankinen, M., Uusitupa, M. & Schwab, U. Nordic Diet and Inflammation—A Review of Observational and Intervention Studies. Nutrients 11, 1369 (2019).

- Yatsuya, H. & Tsugane, S. What constitutes healthiness of Washoku or Japanese diet? Eur J Clin Nutr 75, 863–864 (2021).

- Wang, J., Lin, X., Bloomgarden, Z. T. & Ning, G. The Jiangnan diet, a healthy diet pattern for Chinese. Journal of Diabetes 12, 365–371 (2020).

- Neveu, V. et al. Phenol-Explorer: an online comprehensive database on polyphenol contents in foods. Database 2010, bap024–bap024 (2010).

- Stromsnes, K., Correas, A. G., Lehmann, J., Gambini, J. & Olaso-Gonzalez, G. Anti- Inflammatory Properties of Diet: Role in Healthy Aging. Biomedicines 9, 922 (2021).

- Bersch-Ferreira, Â. C. et al. Effect of nuts on lipid profile and inflammatory biomarkers in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur J Nutr (2024) doi:10.1007/s00394-024-03455-2.

- Calder, P. C. Omega-3 fatty acids and inflammatory processes: from molecules to man. Biochemical Society Transactions 45, 1105–1115 (2017).

- Hewlings, S. & Kalman, D. Curcumin: A Review of Its Effects on Human Health. Foods 6, 92 (2017).

- Whelan, K. & Quigley, E. M. M. Probiotics in the management of irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease: Current Opinion in Gastroenterology 29, 184–189 (2013).

- Lustig, R. H., Schmidt, L. A. & Brindis, C. D. The toxic truth about sugar. Nature 482, 27–29 (2012).

- Medzhitov, R. Origin and physiological roles of inflammation. Nature 454, 428–435 (2008).

- Mozaffarian, D., Micha, R. & Wallace, S. Effects on Coronary Heart Disease of Increasing Polyunsaturated Fat in Place of Saturated Fat: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. PLoS Med 7, e1000252 (2010).